Jack Miller

This past Thursday, the College was visited by Dr. Sylvester A. Johnson, the assistant vice provost for the humanities and founding director of the Center for Humanities at Virginia Tech. He offered the Roanoke College community a seminar regarding the future of technology, the racialized problems that may come with it, and a meditation on the legacy left behind by Roanoke native – Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta Lacks was born in the Roanoke Valley in 1920 and worked for many years as a tobacco farmer. Lacks later moved outside of Baltimore, Maryland where her husband took up work at a steel plant. Upon the birth of her son, Joseph, Henrietta complained about a knot in her uterus. She was tested at Johns Hopkins, one of the few hospitals servicing Black patients in the early half of the 20th century, where she referred to a doctor – Howard W. Jones.

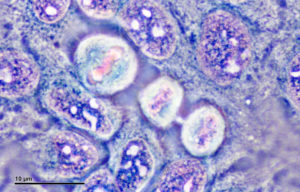

Jones took a sample of a mass found in Lacks’ cervix, discovering that she had an aggressive form of cervical cancer. During treatment for the cancer, two samples were removed from Lacks without her knowledge or consent. These cells were transferred to cancer researchers at Johns Hopkins where they were experimented on. These cells were named the HeLa cell line and formed the basis for biomedical research on cancers. These cells were kept alive, due to researchers realizing that something about them was immensely strong and resilient. Henrietta Lacks’ cells were in fact the first human cells to be successfully cloned and used to study the effects of a multitude of diseases on human cells.

Dr. Johnson explains the glaring ethical problem with the HeLa cells. The shameful, unethical treatment of Lacks broke ethics codes in the process of taking samples from her without constent. This was not all that uncommon for the time; prior to the civil rights movements, few hospitals actually treated African American patients, and those that did often ran unethical experiments on their patients without their consent.

As medicine and technology advances farther into the future and biomedical research continues to develop, we should look to the story of Lacks and the misconduct that she was forced to endure as a dark message for us. Medicine and biomedical progress may be exciting, but we should always be aware that it is built on the discoveries from many uncredited and uncompensated Black Americans. We should, as Dr. Johnson advises, learn from the legacy of Henrietta Lacks and ensure that our pursuit of better technology never again comes at the expense of those who are so often disenfranchised by our society.