Written by Isaac Davis

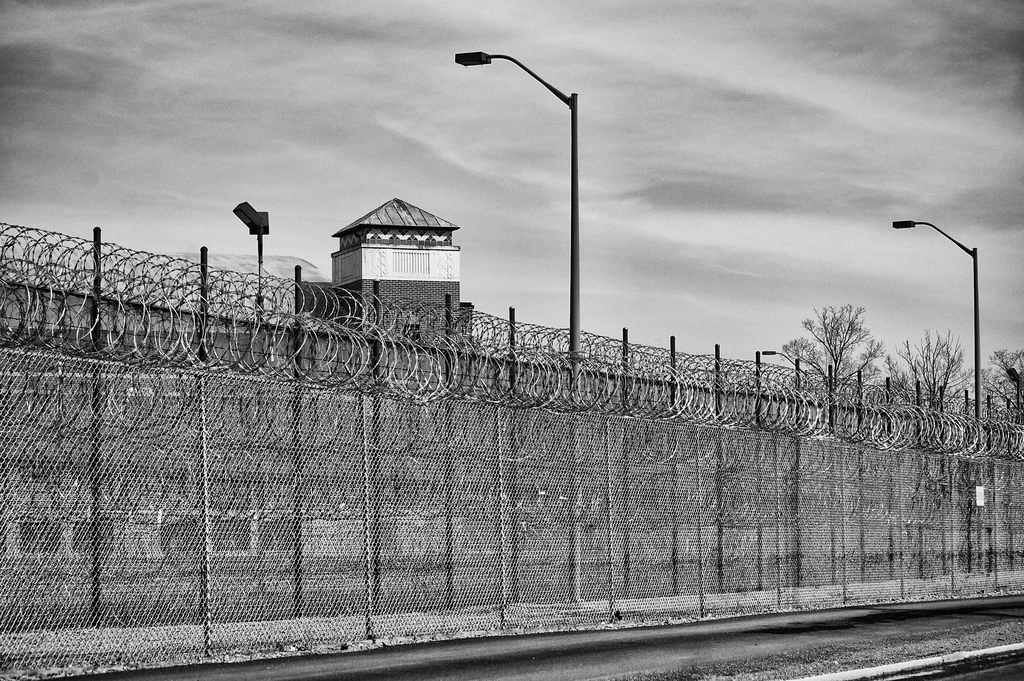

Does our justice system work? Are we safe from the criminals once behind bars?

Within three years of release, around two thirds of ex-convicts go on to further violate the law, and most are within the first week of being released. Why, then, is there such a high rate of failure to state punishment? We must ask how an individual, already prone to anti-social behavior, can be expected to reform an ‘undesirable’ attitude toward life by more intimidation and violence. It does not require a genius to see the obvious flaws in this approach. After years of confinement and boredom, how can that not cultivate further unrest and build hatred for our governing system?

We must also consider our obligation to the criminals. They are people too. Don’t they deserve to be given the best opportunity to break the ‘prison cycle’? Today’s methods are failing the prisoners on this front. They are released impoverished and without any other option than a life of continued crime, creating an expensive cycle that no one benefits from.

Research suggests that most anti-social behavior in prison – and undoubtedly outside – stems from an environment that does not enable creativity, or room to express emotion. Essentially this leads to a bottling effect that accentuates a prisoner’s, or ex-convict’s, general criminal tendencies. At the annual conference of the International Association for Forensic Psychotherapy, leading experts discussed the idea of prison ‘murdering the mind’ of inmates. To combat this failing ‘Art Therapy’ has been further developed and introduced into more institutions. However, improvements are clear to see there are still many prisons without such policies.

Art therapy focuses on allowing expression to be conveyed in a different medium than speech. For prisoners, creating an image is a way of letting out complex emotions in a positive and creative way. Through art, prisoners can visually portray their vulnerabilities without being judged, suffering abuse from inmates, or breaking any laws. Many have not had an educated background and often verbally articulating emotional issues is not easily achievable. The same barrier is met with literary work. The vast majority of cases have issues stemming from their schooling, which are the very memories we do not want to resurface. With art therapy, however, there are no such restrictions. The aims of imprisonment are to show law-breakers the consequences of their actions but equally to re-develop a person into a reformed and law-abiding citizen on their release.

The term art therapy in itself creates abstract connotations, and unfortunately the field is surrounded in a myriad of misconception. Admittedly, it has not been until recent years that this form of psychotherapy has begun to take root, despite the fact that art therapy has been around since the 1940s. Many initial ideas have had the time to be honed into an effective tool, and further research has created what the therapy is today. We are not dealing merely with an ‘outside the box’ idea, but a concrete, tried and tested method. Unlike conventional approaches, one cannot instantly see exterior improvement, but we must remember the brain and subconscious are a complex matter. As such, a personal action is taking place, its benefits can also be hard to witness in the short term. Statistics can provide concrete evidence of its value as inmates exposed to art therapy for a period of three months have been found to be twelve times less likely to be put in solitary confinement in the following year.

Globally, a great number of universities are running art therapy courses, and with more applicants come more professionals, and a greater chance of righting the wrongs of our justice system. Most importantly, we must raise awareness of the flaws of prison and the strengths and achievements of art therapy. This is an issue that affects all of us, and we must consider our obligation to prisoners and think about public vulnerability.